End the Horror, Let the Crisis Change You

"A problem becomes a crisis when it challenges our ability to cope and thus threatens our identity"—it's time our identities adapted

If I say “let the crisis change you,” you might ask, “Which crisis?” It is, after all, the age of the “polycrisis,” an increasingly popular term that attempts to encapsulate the compounded effect of multiple, simultaneous and inextricably bound crises. Whether these are disparate crises or perhaps just one deeply rooted crisis with many sides and many symptoms, the effect is the same: we’re being hit from every angle.

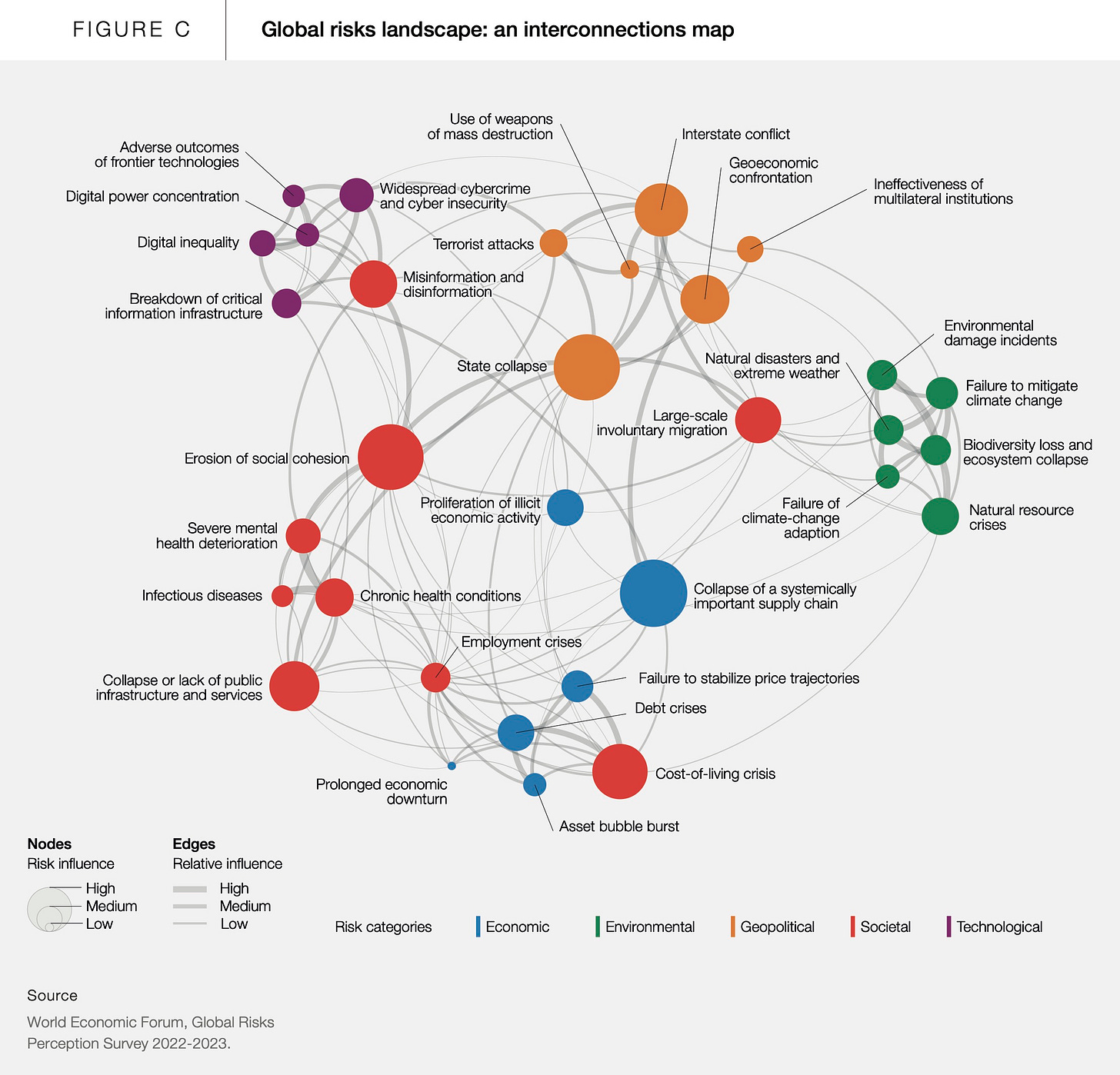

The World Economic Forum explored this encircling feeling of the polycrisis through their Global Risks Report, drawing an interconnected map of risks that spanned infectious diseases, unemployment, mental health, collapse of public infrastructure, climate change, biodiversity loss, food scarcity, interstate conflict, misinformation, involuntary migration, cybercrime, nuclear weapons, AI, erosion of social cohesion, and on and on. In a piece he wrote for the Financial Times, historian (and popularizer of the term polycrisis) Adam Tooze explains, “A problem becomes a crisis when it challenges our ability to cope and thus threatens our identity. In the polycrisis the shocks are disparate, but they interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts. At times one feels as if one is losing one’s sense of reality.”

That feeling of losing one’s sense of reality felt familiar to me. I lived it as I confronted my worldview in the face of climate change and also because, a long time ago, I wrote a horror story. It was for a writing competition where everyone was assigned a random genre, subject, and topic (I got horror, truck driver, and doctor’s visit). As someone who had never written fiction let alone horror, I decided to research what exactly is horror? What are the characteristics of horror stories? How do they make you feel that unique sense of dread?

From what I gathered, horror is largely the feeling we get when confronting the unknown and the inexplicable. What separates horror from awe (another emotion of confronting the "beyond") seems to be that horror is elicited by a loss of sense-making and the loss of control. Horror makes us confront our limitations, our weaknesses in the face of events or beings outside of our control, and worse, outside our ability to even make sense of them.

Horror challenges our “ontological security.” Imagine a cocoon constructed by our worldview, that is our ontological security. Within our cocoons, the universe appears ordered and continuous in regard to our individual decisions; everything we do makes some level of sense. Inside the cocoon, our lives have meaning. In fact, that is the whole point of our cocoons; they allow us to experience positive and stable emotions by helping us avoid the anxiety that would otherwise overwhelm our senses. Horror is when unseen and unintelligible forces, like hyper-dimensional actors, spookily penetrate into what we thought were well-fortified cocoons disturbing our otherwise sensical lives.

The monsters in horror defy everything we previously understood, they invade our sense of safety by challenging our sense of reality. Nothing is scarier than when the walls of reality slip out of our grip, when everything we thought we understood, the rules we so diligently paid service to, melt and collapse before our eyes. Our grasp on reality, our sense-making, is how we navigate the world and ultimately, how we survive. To suddenly lose all bearings and sense of control is to feel adrift in a dark, hostile sea, with no clear enemy, just an all-encompassing sense of dread. A horror movie is not a thriller or an action movie where the enemies are discrete and often easily understood. The enemies of horror are amorphous, everywhere and nowhere, inexplicable, atmospheric. They loom over you in such a way that flight or fight becomes irrelevant. There is nowhere to run and there is nothing quite tangible enough to fight. Horror begins at the edge of logic, at the edge of agency.

It becomes clear that the journey to end the horror is the journey to expand our logic and seek out our agency. Along this path is how the crisis will change us.

To understand the monsters that create crises, we must contemplate hyperobjects.

"Hyperobjects are ‘things’ that are formed by relations among other things, creating new things and that are so vast, complicated and distributed in time and space that we cannot see them or touch them directly as ‘objects’ but rather experience them by looking for their effects and their ‘footprints’ in data patterns, models and discourses." —“The world has become weird”: crisis, natures and radical re-enchantment

According to Philosopher Timothy Morton hyperobjects include things like global warming, the pandemic, all plastic ever manufactured, the internet, and capitalism. In short, big tangly messy things that are often overwhelming in their contemplation.

"Hyperobjects threaten our survival in ways that defy traditional modes of thinking about reality and humiliate our cognitive powers, a disorienting shift that sends many people reeling into superstition, polarization, and denial...

To be hyper is to be or come from beyond... [Hyperobject] was the word everyone was missing, an overwhelming feeling of something so big and complex that you can't see it, even and especially as it surrounds-and often terrifies-you... non-Euclidean monsters of H.P. Lovecraft, creatures so alien and disturbing that to look upon them could shatter the mind.” —Timothy Morton, At the End of the World, It’s Hyperobjects All the Way Down

Hyperobjects, horror, and crises: all are defined by a loss of sense-making.

Together these subjects teach us that there are three common ways to respond when our sense-making is threatened: (denial) hug tighter to your cocoon, (superstition) find simple answer in the form of conspiracy or psuedoscience to satisfy an urgent need to patch the holes in our cocoon, or (deconstruction/reconstruction) let the walls of your cocoon down to make room for a larger sense-making.

Perhaps what we need to hear most when we experience a breach in our ontological safety is that there is sense-making beyond the collapse of our walls. In fact, the horror ends when we begin to see the monsters as they are, when we no longer have to try to make sense of them through the gauzy walls we’ve plastered around our perception. In the movie Signs, the horror is escalated by never catching a glimpse of the aliens—unseen and unintelligible they haunt the ceilings, the edge of our perception. Only after we catch a glimpse of the aliens and learn of their weakness, does the horror begin to end. This is a trivial example but it captures the pattern of horror correctly: only by confronting the hyperobjects, the crises, by increasing our awareness not shutting it down, do we begin the process of ending the horror.

Understanding these forces and responding to their urgent demands might be the greatest challenge of our time, and contemplating hyperobjects, while an often frustrating experience, can be an act of psychological reorientation. Once you grasp them, even loosely, they offer a philosophical escape route from the limitations of our poor little bodies, a way to make sense of a world that no longer makes sense, an alternative to the conspiracy theories and fingers-in-ears denials that have rushed to fill the void." —Timothy Morton, At the End of the World, It’s Hyperobjects All the Way Down

The horrors will continue until we learn to incorporate them into our vision and into our action. So let’s get a bit more specific…

At the core of most of our cocoons are the concepts and frameworks that have been dictated by the sense that capitalism (in it’s more colloquial broader sense that includes deregulation, imperialism and globalization) is the only viable economic and political system. This has been termed a “monomyth” - a singular myth that like a monoculture plantation has carpeted over a rich tapestry of cultures and belief systems, all perpetuated by a dominating Western worldview I will argue is defined by ecological ignorance.

I believe capitalism is actually the proximate cause of these issues but I believe there is a more ultimate cause that stems from ecological ignorance. What we call “capitalism” today (the hyperobject) could only come about in a society that (1) believed it was separate from and held dominion over nature, (2) relatedly, believed that nature was inexhaustible (a foundational assumption in modern economics and the idea that growth can be infinite) and (3) had a cheap and plentiful energy source that allowed it to escape the evolutionary pressure that had defined life on earth until it discovered it (fossil fuels). That evolutionary pressure shaped all human cultures toward energy and resource efficiency and ecological stewardship, but was made temporarily irrelevant by access to an abundant energy source we are blowing through 10 million times faster than it is being created. We are about to face the ecological consequences of ignoring the reality of life on earth for over a century.

"This world is exhausting. Structural and epistemic violence, bureaucratic control, unending crises, and the disenchantment of what Mark Fisher called ‘ capitalist realism’, don’t just warp the ways we experience the world, but can warp and shatter the imagination, foreclosing on possibilities. Silvia Federici talks about disenchantment as constructing ‘a world in which our capacity to recognize the existence of a logic other than that of capitalist development is every day more in question’, a world where all around are enclosures, fences, property, stifling our ability to imagine different ways of being in the world, subjugating values to market value and foreclosing on possibilities and alternative futures.

Mark Fisher explains that the arrival of ‘the Weird’ acts as “a signal that the concepts and frameworks which we have previously deployed are now obsolete” to understand reality. —“The world has become weird”: crisis, natures and radical re-enchantment

The arrival of the “weird”, the arrival of the inexplicable, the overwhelming, the non-sensical, the horror… these are the precise signals we needed to know that our frameworks are failing. That they were always bound to fail, because they were poor approximations of the world.

Do not discount the horror. The horror is the sign. The horror serves to wake us up, to signal our need for new frameworks, new frameworks that could turn the horror into a story with agency. For the instructor of my regenerative economics course, the horror of 9/11 sent him questioning his work on Wall Street and to seek out alternative answers, a path that was only solidified by the financial crisis of 2008. That crisis and the too-big-to-fail debacle should have been enough to signal to us all that the capitalist “monomyth” wore no clothes, but still we couldn’t fight its momentum. If we missed that one, there have been many more. A crisis of housing. A crisis of mental health, addiction, and deaths of despair. A crisis of worker discontent. The 2020 Australian fires. A global pandemic. The 2021 Canadian Heat Dome. The American crisis of policing and for-profit imprisonment. Horrifying self-immolations to draw attention to genocide and climate change. The crisis of wealth inequality. The horrors of last year, 2023, the record-shattering hottest year on record should change us; a horror that continues as our ocean refuses to cool, terrifying climate scientists, not because of the hyperobject of climate change—that’s doing exactly what has been expected—but because of the hyperobject of human inaction.

As awful as these events have been, I am no longer struck by their horror. They all seem to be the near-inevitable, direct effects of how we are running our political economies. I am more struck by our slow ability to react.

It is hardest, I believe, for comfortable Westerners to confront the polycrisis. We have been, for too long, too assured in the progress and stability we’ve brought to the world. We are too invested in the myth, it is too much a part of us. The teasing apart of self and myth will take longer for the people who need it most.

I promise there is sense-making beyond the separation. But the horror can feel like drinking from a fire hose for people’s whose capacity for it has never been trained. All I can advocate for is for us to keep pushing against our cocoons. Don’t shut the horrors out, let them bend you, don’t let them break you or numb you. Keep pushing until the horror ends.

At the very least, it is useful to normalize the feelings of confronting the hyper. It is a feeling many get when first wading into the complexities of climate change or a laundry list of other modern issues. And as far as I'm concerned, there isn't really an alternative, these must be confronted. The question is, how do we navigate that confrontation.

“There’s something about discovering the language of a feeling, being able to name it, that is empowering—a way of finding a handhold in the dim light of confusion rather than scrambling around in the dark.” —Timothy Morton

There is a comfort in knowing the language, it is the beginning of "sense-making" which will turn horror into a more sensible genre. There is also a comfort in knowing this process of confrontation may be the only thing that can save us.

Our limited notion of the world, our ecological blinders, are what caused the crises of today. Could it really be so bad to take the blinders off? We may feel disoriented, blinded by the confusion when we first rip them off, but reach out, grab ahold of someone's hand. There are others already here, finding our way.

Resources for Changing our Frameworks:

(please please please) Read Doughnut Economics

Bonus quotes:

“Sooner or later a false belief bumps up against solid reality usually on a battlefield.” -George Orwell

“It is incontestable that we are in social-ecological systems collapse due to (at least 70 years of) ecological overshoot and deliberately designed and perpetuated social undershoot. The defining question in this collapse-aware systems-context will be, ‘How ought I/we respond to the existential, ecological, and social crises affecting the world?’ And the contest over answers will be dictated by the ecological literacy, capability, maturity, integrative capacity, worldviews and vested interests of those who respond. What is YOURS to do? Who do YOU choose to be?” -LinkedIn comment

Mixed Greens:

Daniel Schmachtenberger “Bend Not Break Part 1: Energy Blindness” -The Great Simplification Podcast

This is why ‘polycrisis’ is a useful way of looking at the world right now - Kate Whiting, World Economic Forum

Are we in the age of the polycrisis? -Jeremy Allouche + more, Institute of development studies

Could a vision for a new economy avoid the polycrisis prophecy? -Matthew Bell

“The world has become weird”: crisis, natures and radical re-enchantment -Amber Huff and Nathan Oxley, STEPS Centre

At the end of the world, it’s hyperobjects all the way down - Timothy Morton, WIRED

Aaron Bushnell’s Act of Political Despair - The New Yorker (a contemplation of the horror of our moment)

Quoting Bertrand Russell - "Most people would rather die than think".

It's a fitting quote because it captures the essence of human nature and ultimately concludes what the challenge for humanity really is - even when we entered into the "polycrisis" era as a collective. I think Daniel Schmachtenberger, John Vervaeke, and Iain McGilchrist did a wonderful discussion on this topic a few months ago. The key takeaway I got from the 3-hour long talk was "we need to make people fall in love with being again". Very true and very hard in the current climate of things.

Polycrisis and hyperobjects are brand new to my lexicon, and helpful words to make sense of these too-big-to-comprehend concepts. Thanks, Spencer. This is an important piece.