Emergencies, Frameshifts and What They Tell Us About Our Place In The World

How becoming a person of place will sustain you in a warming world

Yesterday it was announced that July 2023 was the hottest month on record. It was the latest statistic in a summer of aberrant red lines. First a red column, denoting the area of land burned in Canadian wildfires, ascended far past the canopy of any previous year. Then the sea’s surface started to deviate so dramatically from previous years, my friend who works with NOAA told me his colleagues were convinced something must be wrong with the sensors. Nothing was wrong with the sensors. The ocean has been experiencing an alarmingly unprecedented and prolonged heatwave. For 36 days from July 3rd through August 7th, every day global-air temperature (averaged over the whole earth) was hotter than any day on record in any previous year. The record was previously set in July 2022, but for over 5 weeks, the summer of 2023 laughed at the previous record. To cap off hot girl Earth summer, an equally worrying plummeting red line recorded the Antarctic’s most anomalously low sea ice year on record.

Okay, okay, that was a real rough start. The hottest cold opening there ever was. I’m sorry (haven’t we been through enough?) but I had to set the stage. This summer had me wondering if this was the year more and more people might call this an emergency. And if they did, what would they do?

As someone who has been living with climate as an emergency since 2018, and who has been burnt out (several times) by the effort, I’ve learned a few things about what it takes to sustain an “emergency mindset” and integrate climate-positive behavior despite a cultural and economic system that pushes me in every direction but.

This will take some explanation, but I’ve found the answer is to become a person of a place, of an ecosystem, of a community. It is the only effort that has sustained me and helped override the other, competing frameworks in my life. What are these other frameworks you ask? Let’s dive in…

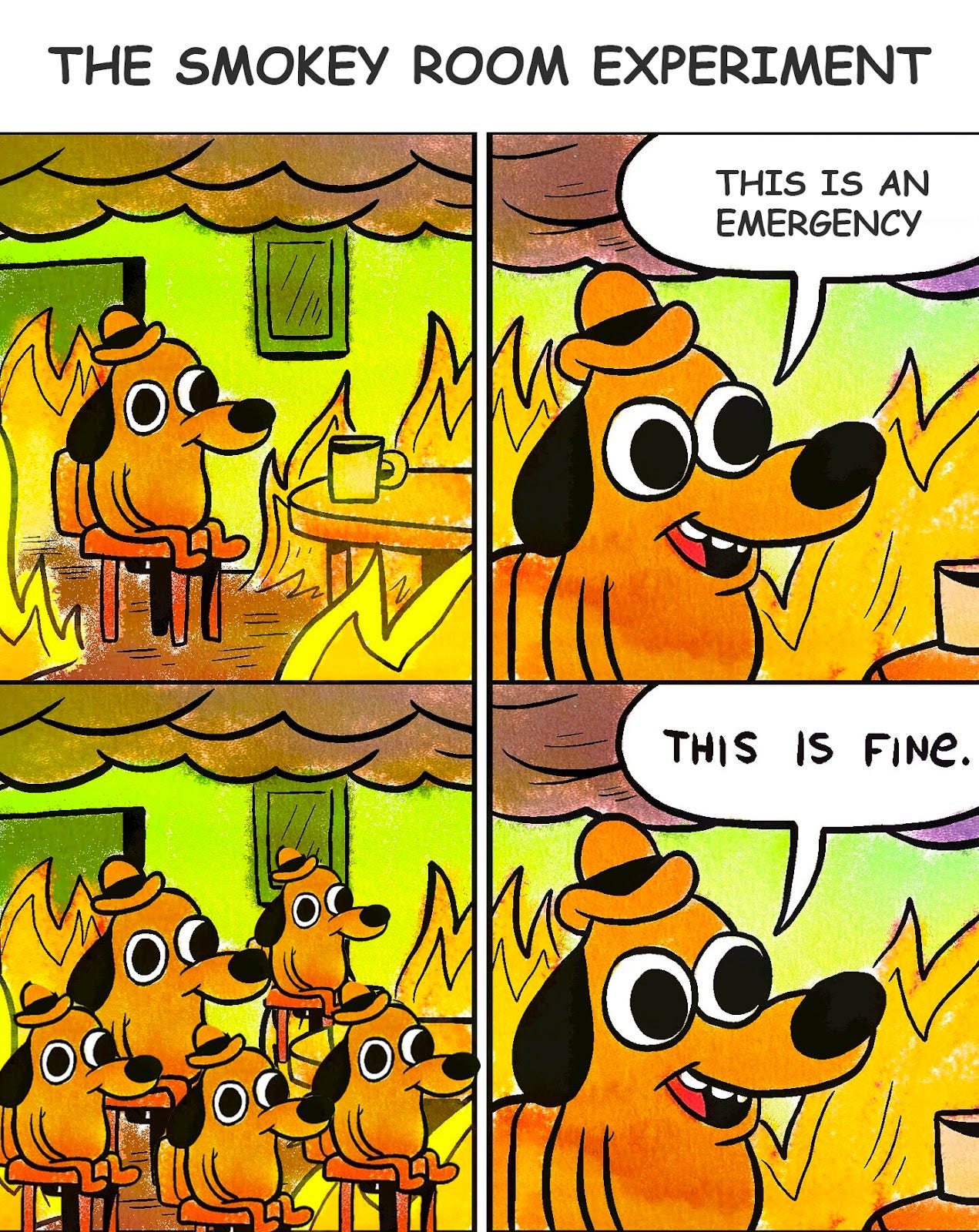

The Smokey Room Experiment

In a classic psychological study, participants were asked to complete forms in a room that slowly filled with smoke. When alone, they noticed the smoke almost immediately but in the company of others, it took them four times longer to react.

This study demonstrates a form of the bystander effect. As social creatures, we wait for “social proof” that a stimulus is worth acting on. We are constantly looking to others to validate “correct action", while never wanting to be the first to act.

Climate writer Chris Hatch put it like this “Psychologists talk about diffusion of responsibility or the need for social proof… a mentor of mine had an earthier explanation: ‘Nobody likes the fucking hippies hanging in the trees, but everyone’s waiting for someone else to pull the fire alarm.’”

From a game theory perspective, this type of behavior can be explained by the potential costs of being an alarm sounder. For instance, there could be a high social punishment for sounding a false alarm (for climate, that risk is gone). Or, even if you're right, there may be a high opportunity cost of acting early. This second reason is where we need to pay attention to what is happening to us. The strain this calculus puts on us.

David Roberts explains it like this, “human beings are not freestanding reasoning machines. They are situated in a world, inheritors of particular socioeconomic conditions, worldviews, dispositions, and interpretive filters. They come complete with a strong set of overlapping, mutually reinforcing frames. To a great extent, those preexisting social and psychological commitments are going to determine how people assess a specific phenomenon like climate change... A lifetime of baggage carries a lot of weight and momentum. Comparatively, a single exposure to a bit of [climate change] framing is nothing, like blowing on the sails of a giant ship.”

There is a social cost to early-moving because all our reward systems are baked into those preexisting mutually reinforcing frames. When we adopt a new frame (e.g. “the climate crisis is an emergency worth our sustained attention”) we put at risk any reward systems in conflict with our new frame.

A climate activist, in the most basic sense, is asking you to shift the relative weights of your frames. They are asking people to rearrange their time/energy/resource allocation to align with a sustained emergency value-set that might be mutually exclusive with many preexisting value sets.

The catch? There is a large social opportunity cost for initiating a “wartime” mentality when your social group doesn’t.

You may face social consequences if you adopt a moral framework that implicitly passes judgement on certain behaviors. For example, meat eaters might feel awkward around vocal vegans, and friends may feel guilty about their recent flight in front of a climate activist friend. Friends are unlikely to abandon you completely, but you may find yourself increasingly isolated, suddenly at odds with a world sailing on different winds.

I, like anyone, can only make decisions based on the relative strengths of all my frameworks. A single strong framework in and of itself doesn’t really stand a chance, it needs to be integrated into a network of frameworks, mutually reinforcing each other.

Even if you hold the climate emergency framework very strongly, it needs positive reinforcement. If the climate emergency framework only brings you unhappiness or social isolation, it will wither. In order for it to be sustained, you need to somehow bring your entire social circle with you (psychologists would call this a social tipping point), or you need to adopt a second framework (and then a third etc.) that positively reinforces climate-aligned behavior until it is intrinsically enjoyable, rewarding, and socially encouraged.

Shifting Frames

The truth is, people don’t give up enjoyable frames until they stop being enjoyable, stop being possible, or there is something more enjoyable on offer.

This is why in Kim Stanley Robinson’s cli-fi book, The Ministry of the Future, he insinuates nothing major will be done on climate until there are massive consequences. In his story, twenty million people die in a heatwave in India which sparks a global social tipping point. After such a disaster, previous frames stop being enjoyable, or at the very least socially fashionable. But such a momentous, singular disaster is more a fantasy since climate is much more likely to be a death by a thousand cuts.

Alternatively, a government declaration of “wartime” mobilization might make an old framework simply not possible. There were only 139 American cars made during all of WWII as manufacturers shifted to wartime production. The year before the war?, three million cars were made.

During the war, you couldn’t value new cars, the structure of society forced the hand of social normativity. Oil rations during the same period spawned a culture of carpooling, and perhaps my favorite government poster ever: “When you ride ALONE you ride with Hitler!” But society only accepts such top-down social forcing in times of mutually agreed emergency, and a war is much more discrete than a generalized shifting climate.

While these may seem to be the most likely catalysts for social change, it’s near essential that we reach a social tipping point before even more catastrophic events occur. Top-down and bottom-up responses to climate are not mutually exclusive, we need both as soon as possible, and a bottom-up groundswell often precedes and precipitates top-down responses.

Technology is one example of bottom-up tactics to supplant old frameworks with better alternatives. There is something very important about this strategy, and it deserves our support but it’s no panacea. Not every problem is a technological problem. For instance, electric vehicles are objectively superior to fossil fuel cars on energy efficiency, but cars, regardless of engine type have a laundry list of downsides. The optimal solution, (e.g. changing zoning and building practices toward walkability and public transit) is often a social issue, not a technological one.

As such, the place we all have the opportunity to participate in the climate movement can be found on the cultural front. Many of our reward systems are socially constructed, which means they draw their power not from some objective source, but from co-created belief. A single person blowing on society’s sails might not shift its course, but a larger and larger group blowing in sync eventually will. Together the climate movement tries to redefine what is aspirational. With every social signal we collectively create culture. What we do and don’t compliment, what we do and don’t share, like, buy, show-off, and so on.

Climate activists, through continued and repeated messaging, hope to reach a social tipping point that changes normativity or social expectations on its own, perhaps even catalyzing the government to take top-down action.

However, if we want to usher in a new way of being, we need not just one framework but also an enabling factor. We must uncover and popularize a new mode of living that feels more enjoyable than the old frameworks (especially in light of knowing facts and information).

Time and time again I keep arriving at the same conclusion, one of the most potent frameworks we can adopt to reinforce climate-positive behavior is becoming a person of place.

Why Being A Person of Place Matters

Like Wendall Berry, I am not suggesting everyone take up farming: “[Berry] has never suggested that everyone flee the city and the suburbs and take up farming. ‘I am suggesting,’ he once wrote, ‘that most people now are living on the far side of a broken connection, and that this is potentially catastrophic.’”

Living on the far side of a broken connection. Living on the far side of a broken connection!!!! Becoming a person of place means drawing closer to things we’ve been estranged from so we can begin a process of reconnection.

One of the larger projects of our modern society and economy is a project of dislocation and disconnection. The more we can untether people into individual units, the easier it is to mobilize them for maximal utility to the market. Most of us are not people of place, we are people of a market. Many move away from our hometowns, we follow opportunity to college or for a job to maximize our economic/career opportunities. Most people do not use their place-based identity as the prism they bend all decisions through, and most people do not integrate into the places they inhabit.

That’s no one’s fault, it was the logic of the system that pushed us into a stream laid out before us. The untethered, after all, are often the “winners” of our economic system, mobilizing to capture value anywhere it can be found regardless of invisible expense to others or the planet. However, the untethered are the losers of the next system, the system that will emerge from the logic of climate change. This new system that will require resilience, which like a spider’s web only claims it’s strength through an interwoven network of strong relationships.

The untethered have a harder time seeing and feeling the harm climate change causes, and abandon any pain that does surface more readily. The untethered will minimize their personal discomfort, moving or shielding themselves from harm, doing little to reduce global risks in the process. In contrast, the place-based can feel the pain but also the benefits of digging in for something they love.

Nobel prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom would explain this as the result of lower discount rates. Discount rates are used to determine how valuable the future is to a person. The closer your discount rate is to zero, the more you equally value the future to the present. Untethered people have high discount rates, they quite literally discount the future, what is the future to them? All their life has been coordinated to maximize present value.

In Ostrom’s words, “Populations that have remained in locations over long periods of time… have shared a past and expect to share a future. They expect their children and their grandchildren to inherit their land. In other words, their discount rates are low. If costly investments are made at one point in time, they or their families are likely to reap the benefits.” Becoming a person of place makes long-term investments desirable, because the future becomes more valuable to you. Those who have committed to a place, an ecosystem, a community, feel those as an extension of themselves. They cheer for their place like a favorite sports team, they envision its success beyond and after themselves.

To the unpracticed this may sound scary, to tether your heart and being to something you can’t fully control. But down that path lies great reward. There are particular joys afforded to being a member of a community, of finding esteem in your peers, of contributing what you can, of seeing wildlife thrive, fruit drip from trees, of being helped by your neighbors when in need, of tangibly witnessing the results of your efforts. The joys and rewards of being a person of place is the missing reinforcing framework for climate positive behavior.

I think we will have a very difficult time integrating the realities of climate change into our cognitive system until we can respond to those stimuli in a way that feels like a net positive. Becoming a person of place allows you to be hopeful, be angry, be defensive, be overcome with fear, and flooded with courage, defiance, and strength. Becoming a person of place will grant you the reinforcing framework to sustain climate-positive behavior and will fortify you with the resilience of a restored connection to the world that needs our attention.

I shared these quotes in an Instagram post, and will share them again: “The formation of intimate relationships depends on four elements: proximity, frequency, intensity, and duration.” “We won’t save places we don’t love. We can’t love places we don’t know. And we don’t know places we haven’t learned.”

If I could impart one piece of advice, it would be to Get Involved. Get Involved. Get Involved. Join a climate group, run for something, try to improve your neighborhood in one single way, then keep going. Entangle yourself with your community and local ecosystem. They need you, and you’ll need them.

Mixed Greens

Is it worth trying to "reframe" climate change? Probably not. David Roberts, Vox.

“[O]n the basis of what we know so far," they write, "policymakers should keep a strong focus on climate risk reduction as the dominant justification" for action on climate change…The one frame for climate change that’s broadly accepted, frequently repeated, and widely understood is that it’s dangerous and we should do what we can to avoid it.”

Social tipping points are the only hope for the climate. David Roberts, Vox.

If there is any hope at all, it lies in the fact that social change is often nonlinear. Just as climate scientists warn of tipping points in biophysical systems, social scientists describe tipping points in social systems. Pressure can build beneath the surface over time, creating hairline fractures, until a precipitating incident triggers cascading changes that lead, often irreversibly, to a new steady state. (Think of the straw that broke the camel’s back.)

What I Stand For Is What I Stand On. Jeffery Bilbro, Plough.

“A handful of dirt may appear inert and lifeless. Nothing, it seems, could be more trivial. And yet nothing is more essential. As Berry writes in The Unsettling of America: “The soil is the great connector of lives, the source and destination of all. It is the healer and restorer and resurrector, by which disease passes into health, age into youth, death into life. Without proper care for it we can have no community because without proper care for it we can have no life.”"

Distraught? Get disruptive. Chris Hatch, National Observer.

“We were really struck by the contradiction between what the public and media say about disruptive protests and what academics said,” summarized James Özden, director of the Social Change Lab. “The experts who study social movements not only believe that strategic disruption can be an effective tactic, but out of all of the factors we asked about, that it is the most important tactical factor for a social movement's success.”

Wendell Berry’s Advice for a Cataclysmic Age. Dorothy Wickenden, The New Yorker.

“I asked him if he retains any of his youthful hope that humanity can avoid a cataclysm. He replied that he’s become more careful in his use of the word “hope”: “Jesus said, ‘Take no thought for the morrow,’ which I take to mean that if we do the right things today, we’ll have done all we really can for tomorrow. OK. So I hope to do the right things today.”

Bonus book recommendation: Lost Connections by Johann Hari

I've forwarded this to at least 6 people and I think I will return to it often - so interesting, so hopeful, so helpful

Lost Connections is the best book on depression that I have found.