The Most Important Thing I’ve Learned About Power

What a Elinor Ostrom, a Nobel prize winning economist, can teach activists

Preface: hi everyone! Sorry it’s been a minute between posts, but I got some really exciting news. A literary agent reached out to me and wants me to write a book. Truly a dream come true. I’ve been busy writing up my book proposal so it’s been tough to find time to write here. However, with the horrific events in Israel and the subsequent (and continued) injustice to Palestinians at the hands of the Israeli government, I wanted to post some thoughts on our relationship to power as citizens and perhaps activists. My thoughts may seem tangential, but I believe they relate to fundamental realities of power dynamics. I hope this has something to offer on how we may best organize and reclaim our power from broken institutions.

From climate change to war, much of the modern human experience seems to be characterized by an anxiety that stems from a sudden need for change confronting the realization that most of us are divorced from any kind of institutional power that could bring about that change. I believe we have a crisis of power and not just the electricity kind, but more fundamentally the organizational and agency kind. As I got deeper into my work as a climate activist, I became concerned with how systems of governance could solve (or hinder) social and ecological problems. Through this search, I came across the work of Elinor Ostrom who fundamentally reorganized my brain around forms of governance (capitalism, socialism, and a secret third option). Her Nobel prize winning work and her book Governing the Commons has given shape to my ecological politics, and I believe that anyone who has lamented their lack of institutional power can benefit from her work.

To preface any commentary on political theory and social change, I was recently struck by a simple premise: that the best and most honest way to pose social change is as problem solving. In his book, Elinor Ostrom’s Rules for Radicals, Derek Wall discusses how Ostrom was not driven by any philosophical doctrine or rigid code in accordance to some “epistemological canon”.

“One rule that radicals can take from Ostrom is that we should reject slogans and broad principles but instead focus on interventions. We want an ecological society, so rather than simply proclaiming this we need to ask what this means in practice.”

Ostrom welcomed complexity, eschewed theory for fieldwork, and was simply a student of what worked. She started, not with a predefined political position but with a question: “How can fallible human beings achieve and sustain self-governing entities and self-governing ways of life, as well as sustaining ecological systems?”

I believe capitalism started, perhaps not with good or bad intentions, but as pragmatic problem solving to a related question to the one Ostrom proposed above. The foundational aspects of capitalism can be seen as a particular strategy set up to solve our most difficult and most universal struggle, which relates to the very nature of our universe and the second law of thermodynamics: that “all of life is a struggle for available energy” (much of that limited energy is then used to struggle for limited resources which can be organized in a way to secure more limited energy… and so on). This is how Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann described the theory of evolution and it generally applies to the organizational principles behind most human endeavors. If this perspective of the world seems bleak, it is perhaps why economics is called the dismal science.

In Hobbes’ famous economics book Leviathan he describes this problem as the “war of all against all” and in Tim Jackson’s book Post-Growth he relates this problem to the Buddhist concept of suffering being inherent to life. Jackson’s goal was to demonstrate, as finite begins in a material world, how universal this struggle for limited resources is from capitalists to Buddhists. He also proposed that we have a choice in how we respond both individually and socially to this problem. We can use institutions to legitimize and mirror this problem or we can use them to challenge and lessen the problem.

This inherent struggle for limited resources is most famously characterized in Garret Hardin’s 1968 “tragedy of the commons”, paraphrased below.

Picture a pasture open to all. It is to be expected that each herdsman will seek to maximize his gain. Explicitly or implicitly, he asks, ‘What is the utility to me of adding one more animal to my herd – balancing the positive and negative component?

The herdsman will receive the full positive component from the sale of an additional animal: the positive utility is nearly +1.

However, the herdsman will only receive a fraction of the negative component because the effects of overgrazing are shared by all herdsman: the negative utility is -1 divided by the number of total herdsman.

Adding together the positive and negative components… the rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible course for him to pursue is to add another animal to the herd… and another… and another. But this is the conclusion reached by each and every rational herdsman sharing a commons. Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit - in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons.

In short, the tragedy of the commons can be seen as the conflict over resources where individual interests and the common good are at odds. Elinor Ostrom is often credited for winning the Nobel Prize for proving “the tragedy of commons” wrong. I’ve seen this often misinterpreted as: “The tragedy of the commons is a myth”, but that’s not quite right either. Ostrom did not dismiss the tragedy of commons, she saw it as a real threat that deserved careful investigation. Through her meticulous and far-reaching research she discovered that the two most common “solutions” at the time: the market (capitalism) and the state (comunism/socialism), were not the only two options.

A huge “a-ha” moment for me was when I realized that capitalism and communism aren’t some morally diametrically opposed forces that signal moral failure or virtue in either party. They are two diverging strategies attempting to solve the same underlying issue. I think it perhaps humanizes our differences and our respectively revered or loathed systems to understand that each system is an attempt to solve our fundamental struggle of being a living organism in a universe ruled by entropy.

Below I’ll explain how each tries to solve the same problem, and why a third way may, mathematically and evolutionarily, be the best way:

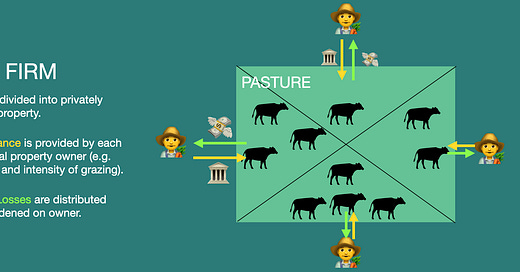

The Theory of The Firm / The Market

The fundamental belief behind market capitalism and private ownership as it pertains to resource management, is that a profit incentive is the best way to turn individuals (at least property owners) into resource stewards. It gamifies people’s self interest in an attempt to align their self interest with long term ecological health.

This structure has two main benefits:

Governance is decided by those closest to the land (if property owners live on and depend on that land). Local knowledge and local decision making are considered important to achieve sustainable results.

Profit incentive can do a pretty good job of maintaining a resource’s long-term economic value (which may or may not include its long-term health).

The drawbacks of this system include:

Resources have less resilience and flexibility when subdivided, i.e. you may be able to sustain more animals (by allowing free movement) on the same amount of land if it’s not divided.

Externalities can be exploited. Externalities are negative effects that escape an owner’s property line, and include things like runoff, pollution, greenhouse gasses, or even harm to employees that is burdened onto society at large.

Distant or disinterested owners can destroy local resources if they are more interested in short-term value capture and less interested in long-term value or health. Economists would call this a high discount rate, which means disinterested owners discount the value of the future; they don’t care what happens to the land down the road.

Another huge problem is… you need a State to enforce private property laws so that your society doesn’t turn into a wild west of constant confrontation over property rights. In economic theory, it would be a huge social cost for each property owner to overinvest in weapons and surveillance. That is the rationale behind centralizing force. Have you ever heard that the police do not protect you, they protect property? This is largely true from a game theory perspective. The primary role of the police in a private-property based society is to pose a threat to deter anyone who may infringe upon private ownership, and punish anyone who does. That threat and punishment is a fundamental ingredient of the type of society the West chose in response to scarcity and the tragedy of the commons.

The Theory of the State

The fundamental belief behind systems of governance like socialism and communism that rely on a strong central state is that the best way to solve issues of resource management is to control those decisions through a central hub. If a ruler can monopolize force, they can coerce their citizen’s activities to produce collective benefit.

The main benefit of this type of system can be seen in the swiftness with which China has been responding to climate change. Often seen as brutal and callus, a central government can make sweeping changes in short amounts of time, relocating an entire town overnight to build a hydroelectric dam for instance. Ostrom characterized a “wise” state ruler as someone who would use their power to increase the well-being of their subjects.

The main Drawbacks include:

Rulers retain the surplus of economic activities which degrades any sense of profit-incentive, and the lack of a competitive market may decrease innovation. Perhaps a reason why China has adopted markets to certain extents.

Distant governance may cause a central ruler to make inappropriate laws or regulations that don’t apply well to local areas. This may cause inefficiencies or active harm.

An obvious drawback is an “unwise” ruler who does not organize their citizens for collective benefit. Such a ruler may destroy the social integrity of their state and cause revolt.

The Theory of the Cooperative & Polycentric Governance

The main operating theory behind the secret third option which we can call The Cooperative is that popular involvement through direct participation made by local people is key to solving ecological problems. Elinor Ostrom believed the more people that were involved in constructing the rules of governance the better the rules would work.

Ostrom believed this because she witnessed it. She found examples around the world from forests in Switzerland and Japan to irrigation systems in Spain and the Philippines that had been successfully communally managed for hundreds of years. What she found by studying these examples, was not that communally managing a commons always works, it doesn’t, what she found was the common recipe for success she outlines as 8 core principles in her book Governing the Commons.

Let’s talk about the benefits:

Governance decisions are made by those closest and most affected by the land. One would expect a group of local people to have low discount rates because they value the future health of their community, and to have local knowledge that allows them to make the most appropriate and informed decisions.

Mutual surveillance increases good/prosocial behavior.

A caveat: one of the core principles of a successful cooperative is “graded punishments” - which means punishments for infractions on the commons start as very minor so that the experience of being in a commons is not one of fear or resentment.

Motivated by profit incentive and long-term health.

More resilience with risk spread across the whole land (e.g. if there is a drought that affects some areas more than others).

The drawbacks:

The main drawback of this theory is the cost of governance. Anyone who has worked in a cooperative knows how difficult and time-consuming communal decision making can be. There is hope that modern tools and knowledge sharing may make this cost less of a burden.

The problem of boundary enforcement remains, since commons still require boundaries. However, if all locals are included in the commons it becomes an internal enforcement issue, and disparities between owners and non-owners are less or nonexistent.

In her theory of The Cooperative, she notes the importance of Polycentric Governance, which is an idea that the structure of the cooperative would be reflected at multiple scales like a fractal. That cooperatives around nearby commons would form a cooperative of cooperatives, and so on, which would allow the creation of a truly representative democracy from the ground up.

Many of us are frustrated with the power dynamics of the system behind the theory of The Firm. Most working people spend half their lives at a workplace where they have nearly no democratic power, and in a political “democracy” that many data points would suggest operates more closely to an oligarchy with public opinion being ignored for the interests of the wealthy.

“That so many people—more than just academics—are questioning the abstract idea of neoliberalism is a testament to both its power failures and its material and cultural failures. But moving beyond neoliberalism will not guarantee a more progressive and democratic economic order or a more racially equitable one; for that, we must not only transform the economy but rebalance power within it.”

John Locke whose ideas, broadly speaking, were the basis for western liberal democracies, believed that the power vested in the government should ensure an outcome of life, health, and liberty, for all; to protect people’s rights ‘as equals before the sight of God.’ In short, he believed that the role of a government, whose power is granted by the people, should be to counteract the struggle inherent to life.

Many human societies throughout history have known this, and societies that operate on the edge scarcity often converge on an ethos of interdependence, redistribution and a organizational theory resembling The Cooperative.

As we approach our modern woes with an attitude of problem solving, I find the lessons of Elinor Ostrom enlightening. I’ve only given a primer of a primer here, but one of the core takeaways is that there are more options than we may have understood and that we should consider what the role of our institutions should be. I believe, if we are to follow what Locke thought, our institutions should be built by more direct involvement, participation, and input by all, and they should function in a way that helps lesson the struggle and suffering imposed by the universe. Through our institutions and our participatory responses to that reality, we can create a society that shares resources and holds us accountable to our better natures.

Recommended Reading:

Elinor Ostrom’s Rules for Radicals, Derek Wall.

Governing the Commons, Elinor Ostrom.

Prosocial: Using Evolutionary Science to Build Productive, Equitable, and Collaborative Groups. Paul W.B. Atikins, David Sloan Wilson, Steven C. Hayes.

Post Growth, Tim Jackson.

Enjoyable reading for a foggy Christmas morning. I like to think about cooperative living and Solar Punk Farms has great appeal! These concepts feel they come from a heart of abundance. I like that this piece illuminates there are more solutions than we knew, and as we feel squeezed by shrinking water supply, negativity about keeping peace etc, it invites us to participate in solutions thinking.

I love the content and would love to read more from you about the commons!