In Search of Effective Activism Part 2: "These Streets Should Be Paved with Gold"

Reversing the extractive flow of wealth from your community

I was hoping to release this essay into a secured Harris presidency, but with Trump’s win, we are entering a much more difficult landscape for social and climate action. Nevertheless, the message remains the same, the work remains the same, perhaps even with one silver lining: there is a chance the left and labor can be united against a more obvious common enemy. The truth is, we are playing a lost game. As filmmaker Damon Gameau pointed out recently, we are living in the endgame of Friedrich Hayek’s neoliberal vision. Neoliberalism, which gained momentum in the 1940s, was built on dismantling worker and environmental protections to enrich a small elite—the “extractive class.” At the root of nearly every modern problem lies the monomyth of neoliberalism, the inequality of power it creates and the environmental and social degradation it causes. If you can wade through everything else as a symptom of this singular cause, it illuminates a path forward: doing everything in our power to keep the value you generate away from the extractive class’s bottomless pit.

We will have to create the real material conditions needed to create an alternative economy. We need ways of generating income that are outside of the current economic system. We have to feed and grow that alternative. We will have to build systems of solidarity that don’t exist in most places. This essay is an introduction to how I’ve been thinking about this task. Please feel encouraged to comment additional thoughts and resources.

In PART 1 of this essay, I explored how social media distracts us from addressing the deeper sources of our discontent. I asked: How can we achieve real, tangible change with the specificity, measurability, and efficacy that Harris Williams urges—restructuring our lives in the process to make a meaningful impact?

Earlier this year, one of my favorite climate newsletters, HEATED, shared the story of James Hiatt, “a third-generation former oil worker from Louisiana who has been campaigning against the LNG build-out for the last two years”. James spent 24 years working at an oil refinery, content with the belief that he was fueling America, until he was wrongfully fired for standing up for an injustice at his workplace. Though he ultimately won a settlement through his union, this experience kickstarted his disillusionment with an extractive industry that mirrored that extractivism onto its employees.

The company always touted “Safety First” but punished people who paused work if they didn't feel safe. It’s a story we’ve heard from many Amazon workers who are regimented inhumanely, and it’s a story we can assume is happening all over the world, even if we can’t see it directly.

This disillusionment led Hiatt to abandon “trading time for a lot of money” and instead chose to become a social worker. After going back to school, he landed a job as a campaign coordinator fighting the expansion of LNG, or liquid natural gas—a conveniently benign term for what can also be called fracked gas.

Though he never considered himself an environmentalist, James’s experience in the fossil fuel industry—and the betrayal he felt—prompted him to look at his community with a newfound skepticism. He had watched plastic facility after plastic facility take over his town, Cameron Parish, and now LNG terminals began moving in, too. Despite all the industry hype about economic opportunity, the wealth was not trickling down. He said his community still “looks like the hurricane we had in 2020 hit yesterday.”

“Come look at Cameron, and tell me if this looks like some prosperous economic development, and not extractive profits for somebody from elsewhere. These streets should be paved with gold. But they’re not.”

In his organizing work, James outlined some of the barriers to progress: people’s livelihoods are bound up in the very industry harming them (“I have friends that work at every one of these LNG facilities”.) He has sen how entrenched cultural views hinder progress (“accepting climate change requires you to become uncomfortable with the way you’re living.”). He deals with corrupted institutions, bought and paid for by the fossil fuel industry (“even our local media is captured by industry”). Still, he persists. He knows the industry will eventually pack up, leaving only devastation behind for the locals to clean up. That motivates him to get up every day and fight them at every front.

It’s so easy to critique capitalism and be dismissed as a cynic or a hater, but let us walk through the argument. No community, given real democratic power, would choose year after year to poison their own air and water. If we accept that, then we must conclude that local people do not control their fate, which is clearly the result of something less than democracy.

Taken in aggregate, this dynamic produces a world increasingly populated with “sacrifice zones”—places sucked of their health to sustain the wealth of a distant few. As this logic has spread across the globe, it leads not only to local exploitation, but to planetary collapse. The extractive class is rapidly eroding the Earth’s regenerative capacity and undermining the resilience of our shared life-support system. In doing so, they put everyone in peril.

The world is teeming with examples of this type of extractivism. A silicon valley AI company KoBold, just made the “exciting” announcement that they found a massive copper deposit in Zambia. The mine is projected to generate billions of dollars in revenue each year for decades. But whether Zambians themselves will benefit, the article notes, “is far from a foregone conclusion.”

Zambia’s Copperbelt Province, where the deposit lies, is already littered with the waste of past mining ventures. Lawsuits accuse companies of environmental devastation, including one alleging that local rivers once ran bright blue with copper tailings. And the article notes, “despite a century of mining, Zambia remains one of the world’s least-developed and most indebted countries.”

Zambian economist, Grieve Chelwa, echoed James Hiatt’s lament about the absence of “gold paved streets”. Chelwa observed, “the value of copper that has left Zambia is in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Hold that figure in your mind [$100,000,000,000s], and then look around yourself in Zambia. The link between resource and benefit is severed.” Copper was being mined in these regions before colonialism, and yet Zambia has seen little to none of the profits. As the New York Times noted, “KoBold’s biggest investors are the heirs of that legacy of inequity. Copper from Zambia helped build the economies on which Silicon Valley fortunes are based.”

If we want to create material change, we have to strike at the root: the staggering and unjust concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. Hearing this may be difficult if the growth and innovation of capitalism are central to your identity and worldview. But we must recognize that whatever merits capitalism may have had, the global economy is now functioning as a “Superorganism”, as described in this incredible paper by Nate Hagens. This entity is driven by an insatiable hunger for energy and continual growth, even at the expense of local communities and the health of the environment it depends on. This Superorganism is following the same biological and physical laws that create cancer. As a former cancer immunologist, this is something I’ve written about before. Growth can be good, but this type of growth has passed the Rubicon into the cancerous, and it will wreak havoc on humanity. And the type of wealth concentration it has spurred erodes democracy, collapses social health, and undermines the stability of the environment.

We must be like James Hiatt—a moth drawn to the flame of injustice. We have to make real, tangible changes to our lives, we have to, as Harris Williams noted, “leave our current pathway.” We may have to quit our jobs, become activists at work, go back to school, start over, rethink, retool.

One of my climate heroes, Colette Pichon-Battle, did just that. After Hurricane Katrina, she left her private legal practice to create the Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy. For 17 years, she has worked to provide relief and legal assistance to her Gulf South community and the lands of her home in Louisiana. In her tenure working for her community, she saw the firsthand effects of “shock doctrine” and “disaster capitalism”, which are the ways in which wealthy people exploit moments of disaster to further entrench disparities. She saw a firesale of distressed real estate, corrupt politicians pushed in by a flood of money, and further entrenchment of the legal and financial power of the fossil fuel industry in the Gulf. Meanwhile, her community was left to suffer. Public education was eroding. Public health care was crumbling. Every shared institution of connection and care was being picked apart.

At the bottom of these predicaments, she could see that the battle wasn’t necessarily in dismantling “big government” but in fighting for who the government serves. Today, our political institutions serve corporations and the politicians who depend on their donations, which is why popular legislation is often sidelined for corporate interests.

Colette Pichon-Battle came to understand climate chaos as the result of this political crisis. Her answer was community organizing. In a political landscape powered by money, we can’t afford to let our value be drained into the hands of those who would sacrifice our health for their bottom line. Colette is part of a growing flank of activists who are spearheading a paradigm shift away from the growth-obsessed Superorganism model and toward a more localized and regenerative economic system.

Her current work was summarized in an interview with Bioneers:

“Studies of resilient communities that rebound from disaster show that government works best when it’s closest to the people it serves. In that light, in 2022 Colette Pichon-Battle co-founded the nonprofit network called Taproot Earth. The goal is to surface solutions from the ground up and to build power across a bioregional network of communities and movements.

Colette launched a series of convenings to hear from the communities themselves and to connect them with each other. They decided their shared goal was to transform systems of governance. That meant moving away from propping up extractive corporate and fossil fuel economies and moving toward democratic self-determination for the greater public good of people and nature. They expanded the map beyond the Gulf South to include Appalachia, and are now working to create a global stance.”

A clear response to this global dilemma is one that communities everywhere, sooner or later, arrive at: we must stop the continual siphoning of locally generated wealth into the gravitational pull of the ever-expanding black hole of the ultra-wealthy. To interrupt that drain, we must understand how wealth is created and how nearly every drop gets wicked away as soon as we create it.

We are facing a very particular problem demonstrated well by this real world example: Employees of an App Formerly Known as Twitter overwhelmingly donated to the Harris campaign. However, their CEO, Elon Musk, as one man to their legion, out-donated them—to Trump—1000x. We’ve set up a political system that is largely run and won on money (90 percent of candidates who spend the most win), and an economic system where 800 billionaires control more wealth than 65 million households. We only have so many winning strategies forward.

In a functional democracy, our advantage over billionaires is that they’re only one vote, in one district. Local politics is your most likely place to make grounds. But with politics so heavily influenced by money, and with a propaganda machine in everyone’s front pocket—our most enduring power is organizational: harnessing collective strength to build resilient structures that keep value circulating within, rather than being siphoned off into the pockets of the wealthy.

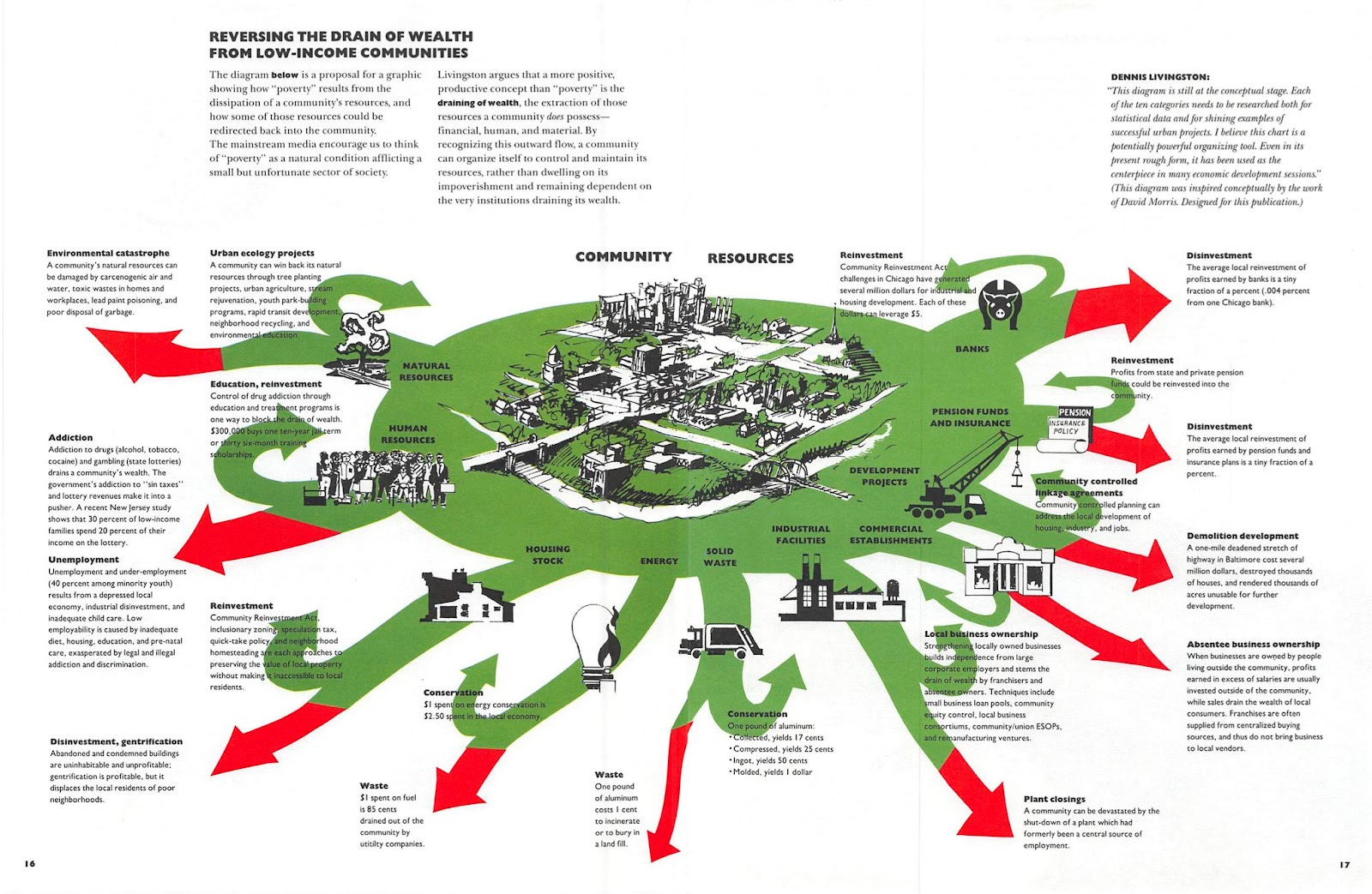

I saved this image from a digital PDF a long time ago, it’s been my laptop background for four years, and mysteriously, despite priding myself on my research abilities, have been unable to find where it came from since. Nevertheless it is a useful jumping off point to think about how wealth—whether in a low-income community or not—is either drained our of or circulated within a community. The font is small, I will walk through its aspects below.

I’ve found it useful to organize these flows through the “Energy, Capital, Labor” lens outlined by Nate Hagens’ Superorganism paper. Energy is the true basis of life. Life exists by “eating” energy and turning it into order. Remember we’re trying to understand how wealth is created. Wealth is “useful order”, and it is created through harnessing energy toward productive purpose.

And although some researchers think only of an ‘energy theory of value’ - where all value is created through energy, Hagens doesn’t think this captures the full picture. “Though capital and labor are both variables dependent on energy, they are each essential in their own right. If you don’t have enough capital (i.e. factories), you can burn as much oil and coal as you want, but will lack the output. If you don’t have the skilled labor to do the job, you will have poor resource productivity.”

In PART 1, I outlined how my journey into activism has circled around the question of “what constitutes effective activism.” I now believe that if you are working in any one of the below areas, working to stop the drain not just away from communities but toward already concentrated loci of wealth and destructive power, your activism is likely to lead to real material change.

In PART 1, I explored how my journey into activism has circled around the question of “what constitutes effective activism.” That inquiry has led me to this conclusion: our most impactful work will interrupt the siphoning of energy, capital, or labor toward already concentrated centers of wealth and destructive power. In doing so, we will create the real material change needed to counteract the extractive logic of the Superorganism and restore the regenerative capacity of local systems.

Energy:

Energy Production

Wealth Drain: Who owns the production of energy, and how far away production is from its point of consumption will determine how much of that wealth is returning to your community. Who you buy energy from also determines the types of companies you are supporting: international fossil fuel companies responsible for untold environmental and social damage being the worst, responsible for wars in the Middle East, Sacrifice Zones in the Gulf South, and murdered indigenous women from Canada to the Amazon.

Wealth Circulation: Local production, from utility-scale to cooperative mini-grids to rooftop solar are some ways to keep that wealth more local, with the obvious caveat that most of these materials are made and mined all over the world. Which is one of the benefits of Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act that aimed to grow domestic manufacturing of renewable energy supply chains. I feel compelled here to note that one barrel of oil contains the work capacity of 4.5-11 years of physical human labor. We need to take alternative energy production seriously.

Energy Efficiency

Wealth Drain: As one example, Americans, with their obsession with large cars and an enforced car dependency, spend over $1000 a month on their car. Europeans spend an average of $370 a month. All those car payments and fuel costs are gushing upward - to car manufacturers, to banks, to insurance companies, to foreign oil, and leaving Americans with less money to circulate in their community. Smaller, cheaper cars, or transit alternatives would lessen the wealth drain. And that’s just transport. Energy efficiency applies across industrial and residential needs for heat and electricity.

Wealth Circulation: As they say, "The cheapest watt is the one that's never created." The less energy you need, through energy efficiency, the more money in your (local) bank. This applies to how big and energy-hungry your car is, how well designed your home is for passive heating, how efficient your appliances are, etc. It also applies to your source of energy: for instance, electricity is roughly 3x more efficient than burning fuels; this applies across electric vehicles, heat pumps, and induction ovens. The less energy we need the richer we’ll be. Energy efficiency is the law of life. Organisms thrive or die on their ability to use energy efficiently.

Capital:

Banks & Finance

Wealth Drain: Big Banks (Chase, etc.) convince you to bank with them for “higher returns”, better points, and better services. They reinvest basically 0% back into your community, and support the worst of the worst from fossil fuels to weapons manufacturers. Let’s help each other stop get unstuck from them.

Wealth Circulation: Move your money to local credit unions or public banks who reinvest back into their community. Friends help friends move banks, and divest from funds that enrich the worst of humanity.

Real Estate

Wealth Drain: Whether commercial businesses or housing, absentee ownership by landlords or private equity firms drains money away from local workers.

Wealth Circulation: Community Land Trusts/Housing Land Trusts are the way forward. Housing is a boon for your local economy, and so is having residents with expendable income. Invest in your neighbors and local workforce, and pin rent or better yet mortgages to a sustainable fraction of a person’s income (<33%).

Commercial

Wealth Drain: All of the wealthiest companies in the world have accrued wealth by becoming more or less indispensable to your life. Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, Walmart, Exxon. Tech companies, Big Box Stores, and Fossil Fuel companies. Together they largely dictate how you shop and how you move around. They are mostly all middle men between where you generate value (income) and where you spend it. They are bridge trolls. They tax that interface, and do not return that money to you or your community. Do your best to drain their wealth by: never buying things from social media ads, unsubscribing from Amazon and buying directly from producers, and in every opportunity support the creation of an alternative economy that uses the resources you give it to treat workers well, care for their communities and environment, and build resilience instead of concentrate wealth in the hands of the few.

Wealth Circulation: Don’t just support local small-businesses because they’re local and small. Support businesses that are playing by more egalitarian rules - worker cooperatives that bring democratic practices to the workplace or businesses with explicit inclusion of community and environment as stakeholders, or businesses that adopt a fair wage ratio between the lowest and highest paid worker. We care about these rules not only because they are egalitarian and lead to more just outcomes, but because they lead to stronger, more resilient, and more enjoyable places to live. You actually don’t have to go full protectionism to support your local economy. Remember that you exist in a web of relation. My small town depends on and is in relationship to San Francisco. San Francisco, a major city, in conversation with the globe. The point isn’t to only keep money in Guerneville. The point is to keep money from places it stagnates in the few grabby hands of the extractive class. I’ll support co-ops the world over before I support a big box store in my backyard.

Natural Resources / “Natural Capital” (Also known as our ecosystems :) )

Wealth Drain: Community wealth is lost when fighting against pollution and externalities that cause environmental damage from poisoned rivers to climate change. This includes poor environmental adaptation that leaves us and our infrastructure vulnerable to floods, droughts, fires, and storms. Adapting to and mitigating these effects will drain your community of its wealth and resilience.

Wealth Circulation: In a climate-worsened future, healthy and resilient ecosystems will pay dividends from increased revenue (more stable yields, more tourism, greater productivity) to decreased costs (cleanup, rebuilding, disaster management etc). Wealth will be built through investment in local ecological health and resilience—including regulating and barring companies that pollute, and investment in conservation, ecotourism, and agroecology.

Labor:

Education/Skill:

Wealth Drain: The de-skilling and miseducation of the workforce keeps people dependent on an extractive system.

Wealth Circulation: Trained, skilled and educated workers are more productive and better resourced to be good community members—the rationale of public schools is that a trained and educated workforce is good for society. The same is true for skill training. It’s in your community’s best interest to fund educational programs to expand local skills/abilities. For instance, we need more electricians. Local efforts to train electricians would be in everyone’s interest.

Health:

Wealth Drain: Unless you’re a multibillion dollar pharmaceutical company or a for-profit healthcare system, healthy citizens are a boon to your economy.

Wealth Circulation: Invest in programs and institutions that care for the health and well-being of your fellow community members. This ranges from locally funded gyms, to restaurants that design their menus to nourish, to creating institutions like child care that provide people the time to take care of themselves. This includes the working conditions that labor movements have fought for since America’s inception: things like weekends, paid time off, safety equipment etc.

Governance: Governance in this framework is about how efficiently our behaviors are coordinated to achieve a collectively beneficial result. It is a hybrid of labor and capital and is about the structures we employ to organize and distribute resources - either at work, or via the government. All governance systems will come at a cost - the fact of nature is that governance comes at a cost. But that cost and the benefits it disburses can be modified.

Wealth Drain: Bureaucratic bloat, underserved services that cost locals in damaging affects of neglect, undemocratic decisions, money flowing from people to points of concentration (i.e. corrupt policies).

Wealth Circulation: People’s wealth, either via profit or taxes are used for mutually beneficial ends such as public works, services, education, infrastructure, housing, or really anything listed above. Better representation at work would include democratic and cooperative decision making and unions that also include community and environmental health in organizational decision making. Better representation at the governance level might include getting money out of politics (public elections), rank-choice voting, or any number of democratic reforms that lead to… well, actual democracy.

As Mandy Harris Williams modeled, when you see injustice, it is your job to very calmly adjust your plans to interrupt it. Here is roughly the shape of the game that is left for us to play. Choose a part, and “lock tf in” as the youths are saying.

If one of these areas particularly interests you, I’d be happy to send you more resources about any of the topics—I didn’t want this post to be any longer than it already is. I think I will create a different post that is all resources, so please send any along you’d like to add.

. . . .

Every community, every individual, holds a thread in the vast, interwoven fabric of resistance. To build a world that thrives, we must reclaim our agency—our right and ability to shape our lives, our communities, and our shared future. The task before us is immense, but so is the strength we possess together. By investing our energy, capital, and labor into systems of mutual aid, community resilience, and ecological stewardship, we can nourish a new paradigm that circulates wealth into our communities and ecosystems instead of draining them dry.

It’s no longer just about recognizing injustice; it’s about choosing, every day, to resist it. Wherever you are, however you can, join in the material work of building, protecting, and sustaining a world worth living in. Pick a role, gather your resources, and let’s continue the work.

Mixed Greens (related reading)

Scarcity to Abundance: How Collective Governance Can Transform the Climate Crisis: Bioneers Podcast and Transcript with Colette Pinchon Battles

Mondragon as the new City-State: Mondragon is decades ahead of American solidarity politics. We have a lot to learn from their example, and this is the best explainer I’ve seen of how they function.

Profits from community windfarm to fund a million native trees in Hebrides: This is what we could be doing with excess energy put to efficient use in creating ordered structures; helping our ecosystems become more resilient. Instead, the direction we’re going is that giant tech companies are brokering deals with novel energy providers to corner the market on new energy production, essentially owning the means of, not labor, but something more primary: energy. Meta with Safe Geosystems. Google with Fervo Energy, ”the world’s first corporate agreement to develop next-generation geothermal power,” and nuclear energy with Kairos Power.

How To Give Away a Fortune: “Redistribution means recognizing that wealth comes from society and should return to society,” she told the council members. She spoke of wealth as power—a power she didn’t earn and doesn’t want.”

Loved this! Did some digging and found where that graphic was from: https://www.academia.edu/44034387/Dennis_Livingston_Social_Graphics. Loving this series

Excellent excellent piece!

Will restack immediately.

J.