Trees are where we start and where we end. Throughout history they’ve stood tall in our minds dripping with metaphor, haunting or redeeming us. They’ve been the origin, the poison, the medicine, and the destination. They’ve been our biggest resource, too much so, and more recently our most promising solution. Today they are our guideposts... our journey begins in the desert.

A Tree, A Church

The Tree of Ténéré, a lone acacia in the Sahara, was once Earth’s most isolated tree — alone for 250 miles in any direction. So prominent in its solitude, it served as a living lighthouse for desert travelers, the last landmark along a hostile salt caravan route. A true symbol of biological resilience, its intrepid tendrils extended to the water table 110 feet below the crusty desert surface. But now it serves only as a symbol of human folly and the destructive force of technology in the hands of the clumsy. The Tree of Ténéré met its fate when a drunk trucker ran it over in 1973. It was replaced with a metal tree-like sculpture so lacking in grace, it’s impossible to not see some parable here on humanity’s current inability to repair damage to natural systems with technological imitations.

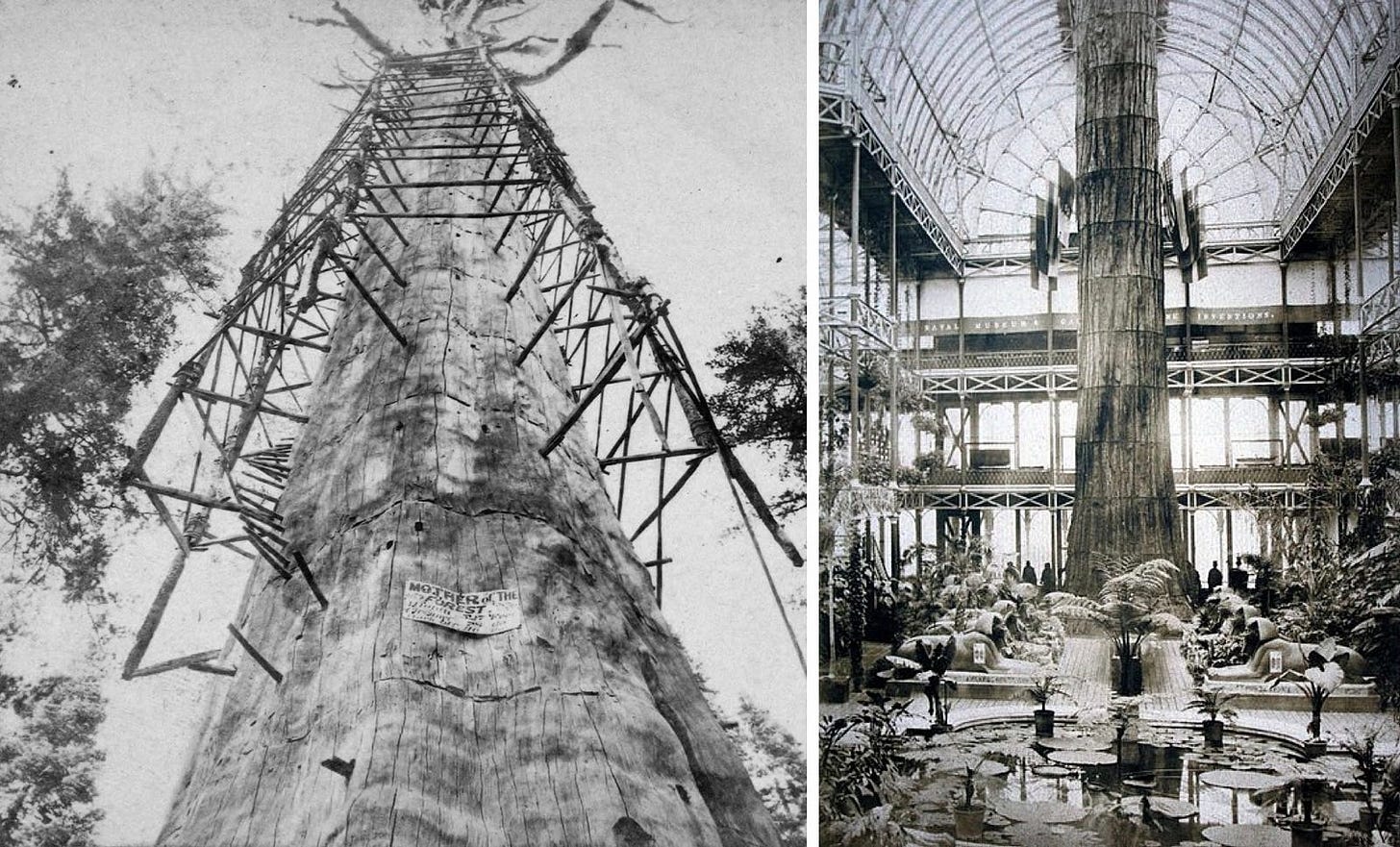

Next on our journey is The Mother of the Forest: a 2,500 year-old Giant Sequoia “skinned alive” in 1852 so it could be reassembled at The Crystal Palace in London. Its exhibition was described as “a financial success”, but back in California, The Mother of the Forest (now looking rather Hellraiser-esque) died within a few years, unable to survive without its bark.

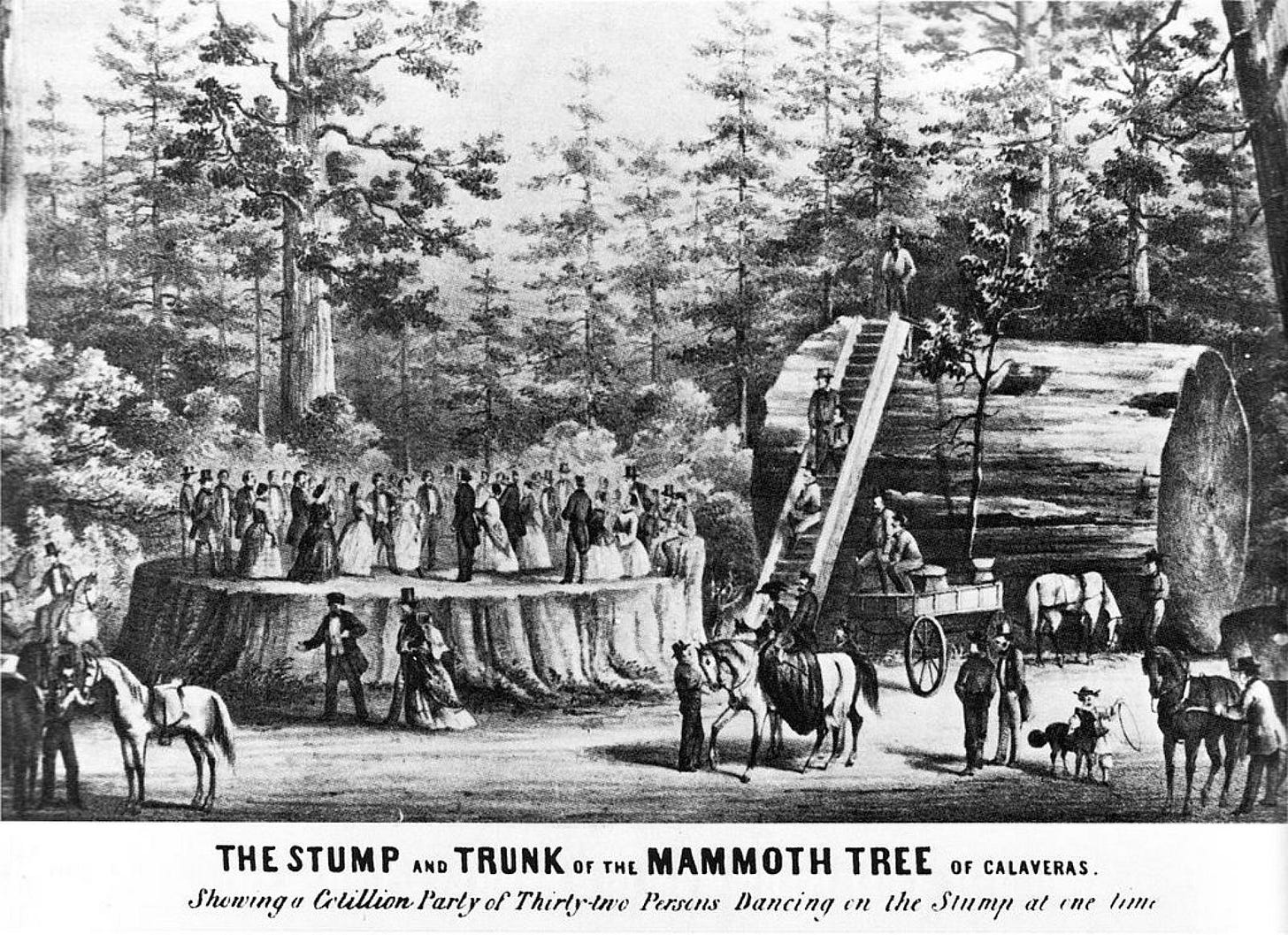

Around the same time and in the same region of what is now Calaveras Big Trees State Park, The Discovery Tree was cut to the ground leaving a 25 foot diameter stump. Atop the stump, the gold rush pioneers held a thirty-two person Cotillion party (can you imagine a stump so large you and 30 friends could foxtrot on it? Can you imagine cutting it down in the first place?). John Muir berated the party-goers in a pricelessly titled essay “The Vandals Then Danced Upon the Stump!”

Then there is the unforgettable story of Prometheus: a Bristlecone pine and metaphor I suppose for the price of careless science. In 1964, a graduate student studying old trees got his core sampler stuck in its dense wood. He cut the tree down to retrieve his tool only to count the rings and find he had just killed the oldest tree ever recorded. At 5,000 years old, Prometheus was a relic of the Bronze Age, soundly predating its ancient Greek namesake by a few thousand years.

But there’s one tree I think about most often: Donar’s Oak, also known as Thor’s Oak. Donar’s Oak was a sacred tree to the Germanic pagans that was cut down 1,300 years ago by Saint Boniface, an Anglo-Saxon missionary. As the legend goes, wood from the tree was used to build a church dedicated to St. Peter.

The reason Donar’s Oak stays with me is its potency as a metaphor for ideological transitions, it’s so visceral and abrupt. For the bones of the old gods to form the body of the new. That is… world-shattering. But there are many of these ideological transitions that prove sometimes that shattering is horrible, sometimes it’s a matter of course, and sometimes it’s an essential act of healing.

A Church, A Shipping Container

Thousands of churches in America die each year, leaving behind thousands of buildings open for transformation. I asked my friends about their favorite converted churches, and woah, people love converted churches. Rave about them.

There is definitely something compelling about making something new out of something once sacred. In the case of Donar’s oak, it’s compelling because it’s tragic. It’s the heightened version of your favorite local restaurant being gutted to build a bland chain store. It’s the old man in Up losing his house to some anonymous business suit.

In the case of abandoned churches across America and the West, I imagine there is a similar pang of loss as churches were sold for secular, often commercial, enterprises. But this succession, although one could argue consumerism is what dwindled church numbers, was not by force but by a gradual dying out and a filling of the vacuum. In either case, it’s something intimate being replaced by some aggressive or unstoppable new paradigm, and in both cases you can see how the old lives on in the new.

Because churches were constructed with certain intentions — to be a gathering place, to be grand in height and ambition, to invoke awe — they incidentally make great places for community. My friends told me about their favorite churches that are now garden museums, breweries, concert halls, skate parks, rock climbing gyms, art galleries, restaurants, nightclubs, even laser-tag arenas. But depending on who is in control, they can just as easily become less community-focused parts of the new paradigm. They become privatized, lose their essence of community, become luxury apartments, office buildings, vessels for commerce, which — in this sequence of metaphors — I’ll equate to shipping containers, you’ll see why.

A man named Carson reached out to me to say he wrote his masters thesis on repurposing European churches. The gist of his research found that segmenting churches and privatizing them (into luxury housing units for example) is the worst use of old churches. It’s best to keep them open to the public and refrain from segmenting them so that their large interiors can continue to encourage walking, gathering, and community building. It’s better to preserve some of the intent of the original structure, and simply guide it to new use.

In the best of cases what can occur is a sort of composting; a church’s essence is metabolized and repurposed to serve a new paradigm. What we start to see is that sacred spaces can be directed in any number of directions, and those new directions reflect our new values. What matters isn’t so much what they were before, but what new life we fill them with.

A Shipping Container, A Tree

We find ourselves at the cusp of another ideological transition. The gods of accumulation and technology are being challenged, as was Dr. Frankenstein, by their own monstrous creation. In this case, the monster is climate change, and it’s giving us an ultimatum to answer to.

What churches of capitalism can we recast in this new paradigm? It seems there is something sacred in our technologies—if sacredness is the result of dedication, attention, and reverence — but can those technologies be composted into good use? How will we repurpose that which no longer serves? What will be the metaphors of this transformation?

The Executive Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute, Amanda Ravenhill, introduced me to one: think of humanity as a newborn baby chick, just cracked out of its shell. Fossil fuels were our yolk, our embryonic fluid — a one time energy boost to launch us from one state to the next. We have emerged into the light with the tools we made in the dark. Our task now is to learn how to use them. You might say we’ve built all the right tools for all the wrong reasons.

I love the metaphor of drones being used to plant trees, I love that computer models built for the military are being used to monitor the climate. I love the redemption arc of San Francisco being re-built after the 1910 earthquake by clearcutting the redwood forests, so it could go on to create technology needed to monitor, track, and reforest the Earth.

Many of these metaphors may be putting too much stock in the saving grace of technology — perhaps it would be more impactful for human hands to be involved in tree planting. Not all of these conversions will result in success, but the trajectory is hopeful.

I love most of all the metaphor Terraformation, a reforestation company, created by turning old shipping containers into decentralized and solar powered seed banks. Access to native seeds turns out to be a surprising bottleneck to reforestation efforts. These modular, transportable sacred vessels to commerce are now being placed in situ so they can help locals reforest their lands.

I love that in addition to the many sad stories of humans and trees, I get to keep this one with me now, too. It helps me believe that regeneration is the unstoppable new paradigm, poised to give new meaning to once-sacred vessels that turned out to be empty in the face of climate change.

If we can learn to repurpose the ingenuity, skills, and tools we’ve built for some wasteful purpose, a composting of the past paradigm into some beautiful new life, perhaps this ideological transition can be the healing of those that preceded it. It can be the returning, from tree to church to shipping container to tree.

Hi, great read! I was wondering, is Carson's thesis on repurposing European churches available somewhere ? I'd love to take a look at it!